While the economic reforms brought rapid changes in Chinese society, political reforms did not follow suit. Many had expected “political opening up” to follow the economy: yet the CCP was very much divided over this issue. Hardliners wanted strict state control whereas more progressive wings of the party hoped for greater democracy. The CCP faced a crisis of identity: on one hand, it had taken the direction to lead China to a full-blown market economy, on the other, as a communist party, it continued to derive its legitimacy from principles of socialism.

Further, China’s nascent market economy was a breeding ground for corruption and sycophancy. It benefitted some people far more than it benefitted others. Nepotism was common during hiring in private companies. There was growing inflation. While China had opened up new universities and educational institutions, it faced a major manpower crunch in various sectors of its economy as the effects of the Cultural Revolution continued to be felt.

Expectations post the reforms were high but there was also increasing discontent. By the mid-1980s, there were protests in many places. Protestors called for greater freedom of speech, removal of censorship, and overall democratization of the Chinese polity. They also expressed frustration over corruption and nepotism in the government and private enterprises.

These protests were often led by students and the youth. College campuses became hotbeds of dissident activities. The first generation of students who had gone abroad to study would often return with new ideas on freedom, governance, and society.

China’s nascent market economy benefitted some people far more than it benefitted others

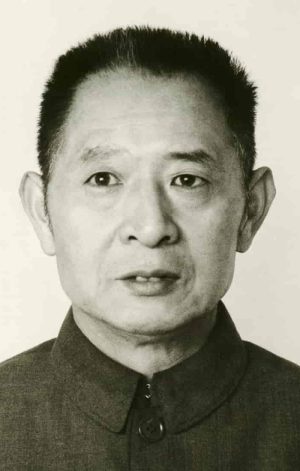

The spring of 1989 saw protests grow in the immediate aftermath of the death of Hu Yaobang.

The spring of 1989 saw protests grow in the immediate aftermath of the death of Hu Yaobang. Hu was a popular leader and the former General Secretary of the CCP. Known for his “liberal opinions”, he was a key player in formulating and executing various reforms that were taking place in China in the 1980s. As protests grew in the mid-1980s, party hardliners blamed Hu’s “bourgeois liberalism.” Hu would speak about major problems with communist economics, human rights, and problems with China’s one-party system. For party hardliners, Hu was a source of much concern. In 1987, he was forced to resign due to his refusal to act against three young communist leaders who openly spoke about the need for political reform in China. His resignation made him very popular among Chinese protestors and liberal intellectuals. He was seen as a martyr of sorts, maintaining the force of his convictions amidst the immense backlash from the CCP.

The protests of the 1980s would come to a climax in 1989 with the Tiananmen Square protests and the subsequent repression by the Chinese State.

By the mid-1980s, there were protests in many places

Protestors called for greater freedom of speech, removal of censorship, and overall democratization of the Chinese society. They also expressed frustration over corruption and nepotism in the government and private enterprises.